Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Physical Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Despite World-Class Institutions and a Sea of PhDs,

India has produced only nine Nobel Prize winners since 1913, with just one scientist (C.V. Raman) winning while working in India in 1930. This modest achievement stands in stark contrast to India’s substantial higher education infrastructure and research capacity. The reasons behind this apparent paradox are multifaceted and deeply rooted in systemic challenges that go far beyond the mere presence of universities and PhD programs.

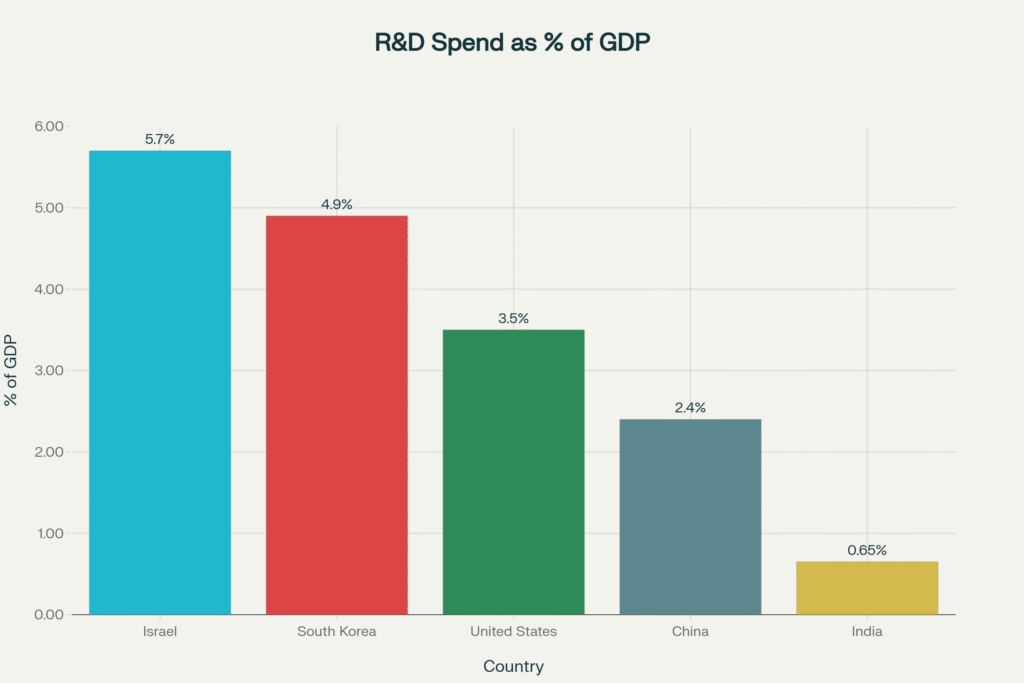

India’s most fundamental challenge lies in dramatically insufficient research funding. The country spends merely 0.64-0.67% of its GDP on research and development, significantly below the global average of 2.6%. To put this in perspective:

This chronic underfunding translates to India’s per capita R&D expenditure of just $43, compared to Russia’s $285, Brazil’s $173, and Malaysia’s $293. Moreover, the government dominates R&D spending at over 55%, while in developed countries, private sector contributions exceed 70%.

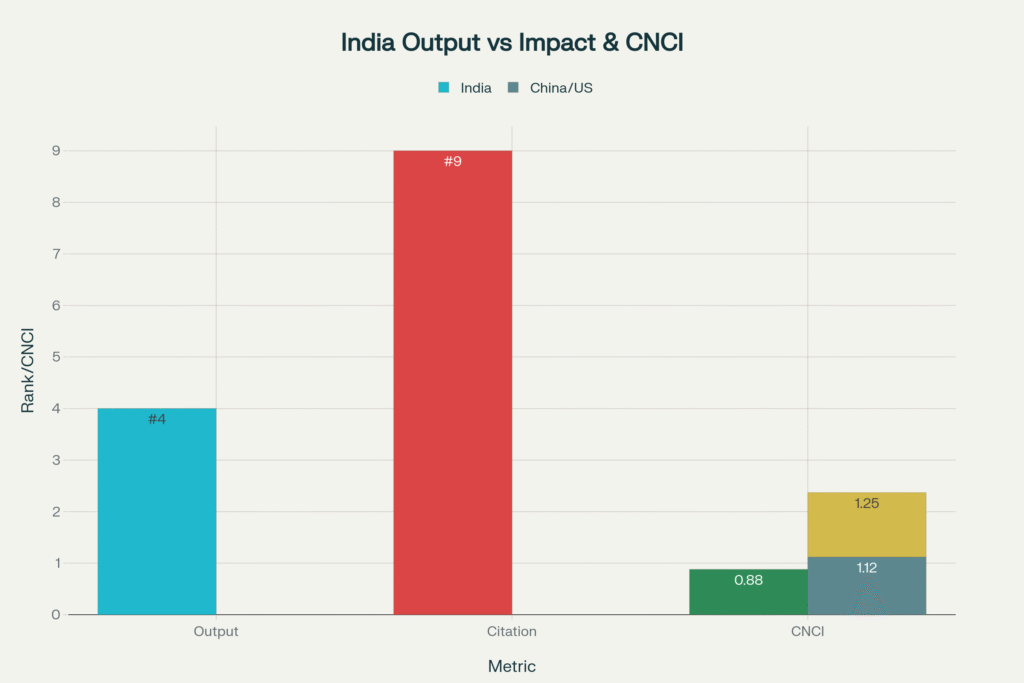

While India ranks 4th globally in research output volume with 1.3 million academic papers (2017-2022), it falls to 9th place in citations, indicating poor research impact. India’s publications rank 28th out of 30 countries in quality metrics, with a Citation-Normalized Citation Impact (CNCI) value of just 0.879 compared to China’s 1.12 and the US’s 1.25.

The focus on quantity over quality is evident in several ways:

India’s research ecosystem suffers from paralyzing bureaucracy. Professor V. Ramgopal Rao of IIT Delhi highlighted that ordering equipment takes 11 months due to excessive red tape. Rigid procurement rules through platforms like GeM (Government e-Marketplace) are designed for routine purchases, not specialized research equipment.

India continues to lose its brightest scientific minds to better opportunities abroad. According to the US National Science Foundation, 950,000 Indian scientists and engineers work in the US, representing an 85% increase over the past decade. This drain occurs because:

Indian universities suffer from a poor research culture characterized by:

Nobel Prize-worthy research requires several elements that India’s system struggles to provide:

Nobel research typically requires decades of sustained effort on groundbreaking problems. However, Indian researchers face:

Nobel committees look for globally significant discoveries that benefit humanity. India’s challenges include:

Nobel-level research demands world-class facilities and equipment. India’s infrastructure limitations include:

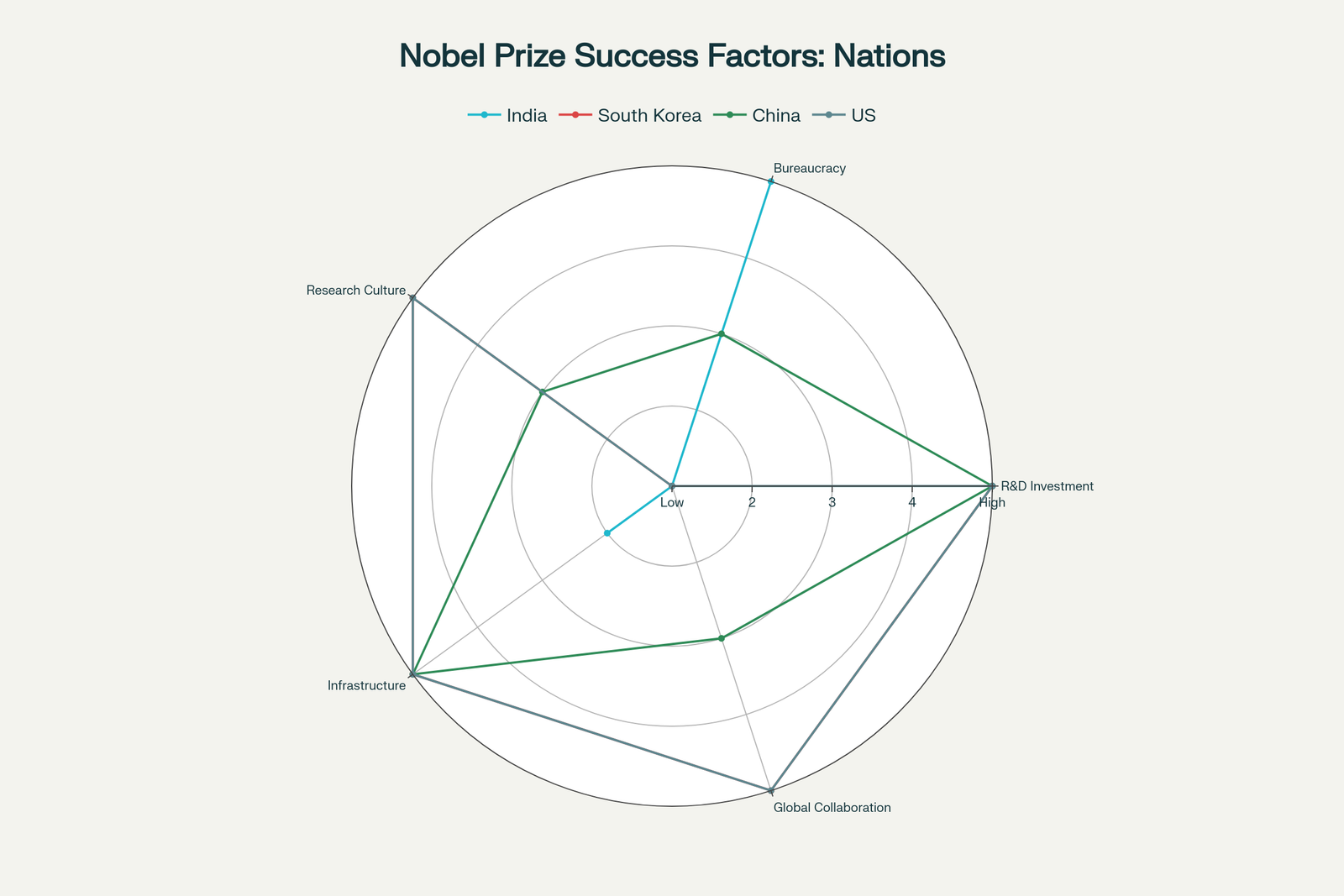

Countries with strong Nobel Prize records share common characteristics that India lacks:

Despite these challenges, there are encouraging signs. Lars Heikensten, executive director of the Nobel Foundation, predicted that “India would not be surprised to get many prizes in the next decade” due to its growing education system and rapid economic development.

However, realizing this potential requires fundamental reforms:

India’s challenge isn’t the absence of good institutions or qualified researchers—it’s creating an ecosystem that enables these talented individuals to pursue Nobel-worthy discoveries. The country has the human capital and intellectual foundation; what it needs is the systematic support structure that allows transformative research to flourish.