Introduction: The Secret Life of a Frozen Continent

When we picture Antarctica, we often imagine a vast, silent expanse of ice—a continent locked in a deep freeze, static and largely lifeless. It is a simple, powerful image of Earth’s last great wilderness, a place defined by its colossal ice sheet. For centuries, this was the prevailing view, a continent understood only by its surface.

But modern geophysical research is peeling back the ice, revealing a world of immense dynamism beneath. Using tools that can sense the subtle vibrations of the Earth and map structures deep within the mantle, scientists are discovering that Antarctica is anything but simple or static. It is a place where deep geological forces, ancient history, and rapid modern changes are colliding. The continent’s bedrock is bouncing back from the last ice age, a massive plume of hot rock may be melting it from below, and its most vulnerable glaciers are generating their own strange seismic signals.

The following five points uncover some of the most surprising and impactful secrets of the continent, from its deep structure to the strange seismic signals it emits. They paint a new picture of Antarctica: a continent in motion, whose hidden mechanics are critical to understanding our planet’s future.

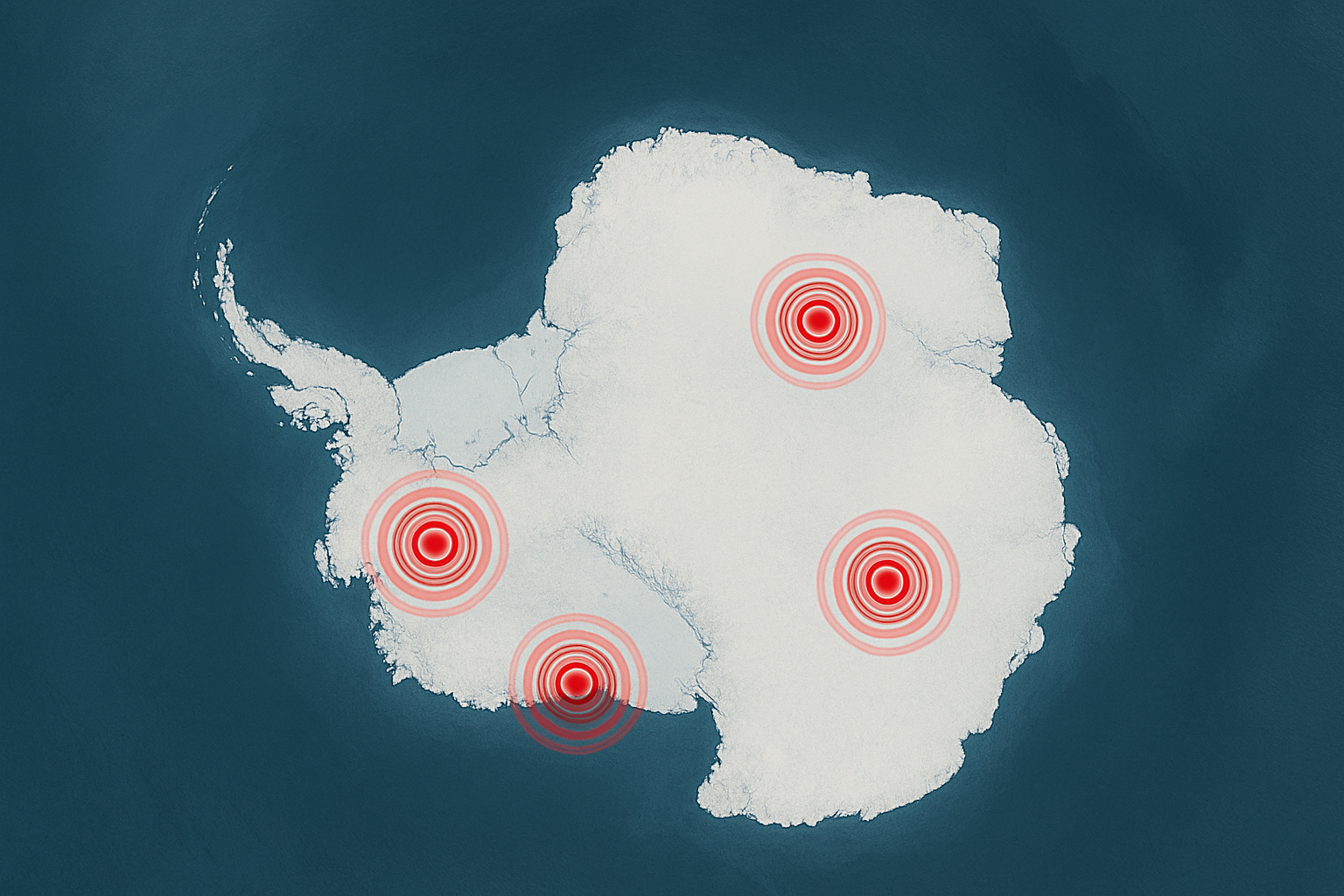

1. It Experiences ‘Glacial Earthquakes’ at its Most Feared Glacier

While we typically associate earthquakes with the grinding of tectonic plates, glaciers can generate their own powerful seismic events. A “glacial earthquake” is created when a massive, tall iceberg breaks off from the edge of a glacier, falls into the ocean, and capsizes, clashing violently with the “mother” glacier it just left. This impact generates strong seismic waves that can travel for thousands of kilometers.

What makes these quakes unique is that they do not generate the high-frequency seismic waves typical of tectonic earthquakes. Because of this, they were only discovered relatively recently, despite decades of routine seismic monitoring worldwide. While most previously detected glacial earthquakes were in Greenland, a new study has found hundreds of them in Antarctica between 2010 and 2023, concentrated at the Thwaites Glacier. The largest of these events are comparable in size to the seismic signals generated by nuclear tests, making them significant geological phenomena.

Famously known as the “Doomsday Glacier” for its potential to rapidly raise sea levels if it collapses, Thwaites is a focal point for climate research. The most surprising finding is that, unlike in Greenland where these quakes are seasonal, the most prolific period of glacial earthquakes at Thwaites (2018-2020) coincided with an independently confirmed acceleration in the flow of the glacier’s ice tongue toward the sea. This suggests a direct link between these seismic events and the glacier’s growing instability.

2. It Isn’t One Continent, But Two Fundamentally Different Landmasses

Beneath its unifying sheet of ice, Antarctica is not a single, uniform block of rock. Seismic tomography reveals a continent with a “bimodal nature,” composed of two fundamentally distinct geological provinces: East Antarctica and West Antarctica. The division between them is one of the most striking features of our planet’s crust.

East Antarctica is predominantly an ancient, stable Precambrian craton—a solid and deeply rooted piece of continental core. Its structure is similar to the ancient hearts of other continents that once formed the supercontinent Gondwana, such as those in present-day Africa and Australia. In contrast, West Antarctica is a much younger assembly of different tectonic provinces, stitched together over geologic time.

This division is not a gentle transition but a “sharp boundary” that runs along the Trans-Antarctic Mountains, a range extending over 3,200 km across the continent. At a depth of around 100 kilometers, the contrast in the speed of seismic shear waves across this boundary is as high as 17 percent—a dramatic difference that speaks to the profound structural split. This fundamental divide influences nearly every aspect of the continent’s behavior, from the flow of geothermal heat from the mantle to how the landmass responds to the immense weight of the ice above it.

3. A Mantle Plume May Be Melting It From Below

One of the most dramatic forces shaping West Antarctica may be an upwelling of abnormally hot rock from deep within the Earth’s mantle, known as a mantle plume. Using seismic tomography to create a 3D map of the mantle, scientists have identified a deep-seated low seismic velocity anomaly directly beneath Marie Byrd Land in West Antarctica. Slower seismic waves are a key indicator of hotter, less dense rock, and this feature is consistent with the presence of a mantle plume.

This finding helps explain other long-observed features of the region, such as its high topography and history of Cenozoic volcanism. The heat and buoyancy from a deep mantle upwelling provide a compelling mechanism for both lifting the land and feeding magma to the surface—a process thought to have begun some 20 to 30 million years ago.

The implications for the ice sheet are significant. A mantle plume would result in higher geothermal heat flow to the base of the ice. This heat affects the basal temperature, which can increase melting at the ice-bedrock interface and influence the rate at which the ice flows towards the ocean. This hidden heat source adds another layer of complexity to understanding and predicting the future of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet.

4. It’s Still Bouncing Back From the Last Ice Age, Complicating Everything

Thousands of years after the end of the last Ice Age, Antarctica’s bedrock is still slowly rising. This process, known as Glacial Isostatic Adjustment (GIA), is the “viscoelastic” response of the Earth’s crust and mantle to the melting of the unimaginably heavy ice sheets that once covered it. Imagine a memory foam mattress very slowly regaining its shape after a massive weight has been lifted—the Earth is doing the same thing, but on a continental scale over millennia.

While it’s a fascinating geological process, GIA is a critical and complicating factor for modern climate science. To accurately calculate how much ice Antarctica is losing today and how much that loss is contributing to sea-level rise, scientists must precisely model this ongoing land motion.

Measurements from satellites like GRACE and its successor, GRACE-FO, which track changes in Earth’s gravity field to weigh ice sheets, and from high-precision GPS stations on the ground, record both the signal of modern ice loss and the signal of GIA. The GIA component must be carefully calculated and subtracted to isolate the present-day climate signal. As one study on Atlantic Canada highlights, correctly accounting for GIA is essential for improving projections of future problems like coastal nuisance flooding, demonstrating how this ancient process has very modern consequences.

5. That ‘Bouncing Back’ Could Be a Surprising Braking System on Ice Loss

While the rapid loss of ice from Antarctica is a major concern, the Earth’s response to that loss may provide a surprising, counter-intuitive brake on the process. The same GIA process that complicates measurements can also create a powerful stabilizing feedback loop.

The mechanism is straightforward: as an ice sheet loses mass, the bedrock beneath it uplifts. According to recent research, this effect is particularly pronounced in West Antarctica, which is underlain by a weak, less viscous upper mantle. This allows the bedrock to rebound much more quickly to changes in the ice load compared to regions with a more rigid mantle.

This rapid uplift has a critical consequence for marine glaciers at their “grounding line”—the crucial point where the glacier loses contact with the bedrock and begins to float in the ocean. As the seafloor rises, it can lift this grounding line, effectively making the water shallower. This shoaling can act as a natural brake that slows the rate of the glacier’s retreat. This discovery shows that the solid Earth is not a passive stage for climate change but an active participant that can, in some cases, work to stabilize the ice sheets above.

Conclusion: A Continent in Motion

Antarctica, far from being the static continent of popular imagination, is a complex and active system. Deep Earth forces, ancient geology, and modern climate change are constantly interacting in ways we are only just beginning to understand. Its bedrock is a mosaic of ancient cratons and younger terranes, it is being pushed up from below by mantle plumes, and it is still breathing a slow sigh of relief from the weight of the last Ice Age.

These hidden dynamics are not just geological curiosities; they are critical components of the global climate system. The stability of glaciers may depend on the viscosity of the mantle beneath them, and our ability to measure sea-level rise depends on our understanding of a process that began thousands of years ago. As scientists continue to uncover these hidden dynamics, the key question remains: will these complex feedback loops slow Antarctica’s melting, or will they trigger unforeseen tipping points in a warming world?